In 1653, most British churches were being smashed up by Roundheads. But in Leicestershire, one was being built ...

For those who know their history, the Chapel of the Holy Trinity, in Staunton Harold, Leicestershire, stands as something of an anomaly.

As churches go, it's nothing too special. A fine example of Gothic revival architecture, but there are plenty others which are more ornate and/or more impressive in that style.

The eye-opening part isn't how it was constructed or what it looks like (a conventional village church), but when it was built. Between the outbreak of the English Civil War and the Restoration, churches were generally knocked down or smashed up.

Except one.

Its youthful founder didn't live to see it completed. The Royalist rebel died in the Tower of London, locked up under orders from Oliver Cromwell.

Sir Robert Shirley, 4th Baronet Shirley of Staunton Harold

He was just seventeen years old when he received his peerage.

But you have to make your mark, don't you?

Most teenagers think that they have it tough, but Sir Robert Shirley might be forgiven a few moments of quiet reflection.

He was only three years old, when his father died. His nine year old brother, Sir Charles, instantly became the 3rd Baronet of Staunton Harold. This was 1633 and their world was becoming a dangerous place.

Seven years later, their uncle, Robert Devereaux, 3rd Earl of Essex, was instrumental in starting the English Civil War. This placed the family's political sensibilities firmly on the side of the Parliamentarians. But nothing is ever that simple.

The Shirley's had been devout Roman Catholics throughout the Tudor period. They maintained their faith, even when it was subject to high penalties. But Henry Shirley, the father of Charles and Robert, had had enough. He allowed his sons to be raised in the Protestant faith of their mother, Dorothy Devereaux.

Nevertheless, the spirit of rebellion hung around Staunton Harold Hall. There were many whispers about the Baronet taking in dispossessed Catholic and Anglican priests, even as late as the Civil War period.

For young Robert, this was all background, adult stuff. He was packed off to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, as soon as he was fifteen. A year later, he was married to Katherine Okeover and simply moved her into his student quarters at the University.

Then, in 1646, as it seemed the whole country was falling to the Parliamentarians, Sir Charles Shirley died of smallpox. He was just twenty-three years old. His seventeen year old brother had the peerage and the tumultuous responsibility of it all.

Moreover, in September of the same year, The Earl of Essex also died without an heir. Sir Robert Shirley suddenly found himself nominally the 13th Baron Ferrers of Chartley. But the title was held in abeyance.

Cromwell and the late Earl of Essex had severely fallen out.

Royalist Sympathies at Staunton Harold Hall

Sir Robert Shirley was passionate about Laud's Church of England; and he was also indicating support for the monarch.

The overriding impression of Oliver Cromwell tends to be of a bit of a tyrant. He led a regime which banned everything, while also wrestling government away from the crown.

In reality, he was far more tolerant than some past monarchies; while not nearly as hot on democracy, as some would like him to be remembered.

Puritan Roundheads did go around the country smashing the vestiges of Catholicism from British churches. But on the other hand, the Commonwealth government did allow more religious freedom than before. There was one very strong condition. The spiritual expression must neither criticize, nor be a threat to, the Parliamentarians.

In Staunton Harold Hall, the young Sir Robert Shirley had embraced Laudian Anglicanism. Of all the Protestant denominations, this was the closest in actuality to Catholicism. It was an early indication that he was prepared to edge around the limitations of Parliament's edicts.

Robert had also returned home from college, with his wife, and the teenager was aching for some action in the war. His brother, Charles, appears to have been a quiet man. The First Civil War didn't hugely impact upon their estate. But Robert was much more feisty.

However, there wasn't a great deal going on; and nothing in Leicestershire. Sir Robert Shirley didn't have many battles that he could have fought in, so his sympathies did not publicly come to the fore until 1648.

Now aged nineteen, he was involved in a drunken fight outside Ashby Castle in nearby Ashby de la Zouch.

The 'malignants' in his company certainly appeared to be Royalist, and they were clashing with soldiers in front of the Parliamentarian owned castle. But that was it. It was a very small fracas, rather than a full blown battle.

Sir Robert Shirley was escorted under armed guard back to Leicester County Court. His prosecutors tried to make him out to be the leader of a Royalist underground movement. His defenders dismissed him as a kid who had drunk too much. The court appears to have thrown the case out.

Then, in April 1650, Robert's signature appeared on a petition denouncing the execution of King Charles I. The same document declared lack of support for the Rump Parliament. Robert's entire estate was seized by Cromwell's forces; and he was thrown into the Tower of London.

Sir Robert Shirley in the Tower of London Part One

This young man certainly knew how to appeal to a cash-strapped, war-torn Parliament!

The Tower of London has been housing England's political prisoners for nearly 1000 years.

In May 1650, Sir Robert Shirley was just the latest of them.

Now in his twenty-first year, his Royalist sympathies were no longer in doubt; nor did he try to deny them.

However, he was an erudite man and an alumni of Cambridge. He knew how to pen a letter that would win round other peers, like, for example, those who held the key to his Fate in Parliament.

His first letter made no mention whatsoever of his possible release. It merely made reference to all the death duties that he wouldn't be able to pay to the State. There was all that inheritance from the will of the late Earl Essex for a start.

Almost as a secondary concern, he talked about the affairs of his estate. All those tenants relying on him...

When that failed miserably, Sir Robert wrote further letters. This time he was worried about fulfilling his other responsibilities. As a land-owner and a peer, he was supposed to be raising a militia to fight for Parliament. He couldn't do that stuck in the Tower of London.

After five months of this, someone must have just given in. Sir Robert Shirley was released from the Tower under certain conditions. He had two securities of £5000, which would be payable if he messed up again. He also had to stay put at Staunton Harold and not join any Royalist movements. Professing loyalty to Cromwell and the Commonwealth, Robert went home.

Discrimination Against Staunton Harold's Cromwellian Tenants

It only took two years for Sir Robert Shirley to end up in court again.

The Council of State records for December 10th 1652 include a familiar name. Sir Robert Shirley was standing in front of it answering more allegations.

Nine of his tenants had spoken up against him. They claimed that, despite working hard on the Shirley lands and paying their rent on time, they had been victimized. The Baronet had made life difficult, before evicting them to give their holdings to other families.

Without exception, the nine plaintiffs were Parliamentarians. They supported the Commonwealth in all that they did. One of them was even a Civil War veteran, having fought for Cromwell. Those moving into their homes were Royalists.

Sir Robert argued that they were trying to frame him. Each person had a reason for wanting him removed, which did not involve the Parliamentarian cause. They'd ganged up on him to damage his reputation.

Remarkably, the Council of State believed him.

Gun-running for the Sealed Knot

Emigres in the American State of Virginia were supplying the weapons.

Sir Robert Shirley was storing them.

By 1653, Sir Robert Shirley appeared to have settled down.

Apart from that incident with his tenants, he was living the life of a responsible husband, father and stately gentleman. He had two sons by now. Seymour, born in 1647, and Robert, born in 1650. All looked very sedate.

At least, it did from the outside. For those in the know, Staunton Hall was becoming filled up with guns and other weaponry.

It was all being collected on behalf of the Royalist movement, the Sealed Knot. Businessman Henry Norward bought the arsenal in Virginia, then smuggled it into England. An agent named Rowland Thomas took the arms across country and delivered them to Staunton Hall. Sir Robert Shirley stashed them away until the time was right.

It's also undeniable that Robert was a prominent figure in the Royalist activities throughout the East Midlands. Perhaps he was even the main co-ordinator for the Sealed Knot there. Intelligence reports were buzzing everywhere. Daniel O'Neill, working for the exiled Charles II, wrote to the monarch that a 'good example' could be found in Sir Robert Shirley.

Meanwhile, Cromwell's spies strongly suspected that the baronet had contributed food, horses and part of his own personal fortune to the Royalist cause.

The trouble was proving any of it! Then Robert did something that was as blatant as it was possible to get.

It was time to build the only church constructed in England since the outbreak of the Civil War.

The Building of the Chapel of the Holy Trinity.

This is better known to us now as Staunton Harold Church. It was undeniably built as an open act of defiance against the Parliamentarians.

Holy Trinity looks medieval in its construction. The design is a Gothic revival style, with some Baroque elements.

Buttresses and turrets line the outer walls. Ornate stained glass fills every window and icons stand above the door. The pews are Jacobean. Their cushions, and the altar cloth, are both purple velvet. In short, it looks Catholic, even to modern eyes.

In context, any surviving Catholic traces were being destroyed in every other church in the land. But this wasn't meant to be 'Popish'. It was determinedly and dangerously representing Laudian Anglicanism.

As well as the rebellious inscription above the door of Holy Trinity, there is a second one at the rear. It flanks the battlements around three walls and reads:

"Sir Robert Shirley Baronet founder of this church anno domini 1653 on whose soul God hath mercy."

He wanted there to be no mistake about who had built the Chapel of Holy Trinity. Nor could the protest message be missed. Inside the church, the ceiling was painted with English Baroque finesse. All of the elements are represented, as is the Trinity.

The Tetragrammaton is proudly displayed, which is a provocative inclusion. The 'Name' was considered so holy that it could not be shown in Catholicism, nor uttered in Judaism. (As recently as 2008, the Vatican issued a directive that 'Yahweh' could not be spoken in liturgy. This controversy isn't confined to the 17th century.)

But Sir Robert Shirley was an avowed Laudian Anglican and there was history with the Tetragrammaton. Archbishop Laud was put on trial in 1642, charged with including Catholic iconography in his own church.

In his defence, he pointed out that a woodcut, from the title page of the Book of Martyrs, featured a Tetragrammaton. It had just been published in a new edition and no-one had blinked about that. He had included nothing worse.

This argument did not save him. He was beheaded on Tower Hill in 1645. But it had been a famous statement, and now Sir Robert had placed the same symbol in his church. That wasn't all. The ceiling art also featured Cromwell as a black dog, poised to pounce upon the Holy Trinity itself!

Around the edges were depictions of the ocean, in waves or sea-shells, which were probably an oblique reference to the exiled King Charles II.

The whole building was enough to have Sir Robert Shirley instantly arrested. That he wasn't showed that the Parliamentarians needed him to be free. Their intelligence agents were watching him very closely indeed.

Penruddock's Uprising Fails to Inspire Leicestershire Support

The Sealed Knot said it was too soon, but Sir Robert Shirley forged ahead anyway.

In December 1653, the gun-runner Rowland Thomas visited Staunton Harold Hall. He wasn't alone. The steward's records show that there were many house guests over the winter.

This wasn't too unusual for a gentleman's stately home during the festive period, but for the names involved. They were known Royalist sympathizers. Nor were their meetings confined to the baronet's home. Sir Robert Shirley was spotted at an ale-house, in Betley, Staffordshire. The discussion there had been an uprising, which would have taken Chester for the Royalists.

By Christmas 1654, Rowland Thomas was actually staying in Staunton Harold Hall. Activity went into overdrive.

On March 8th 1655, everything came into sharp focus. Suddenly the arsenal stashed at Staunton Harold had been distributed to factions all over the country; and the Royalist leaders were riding out.

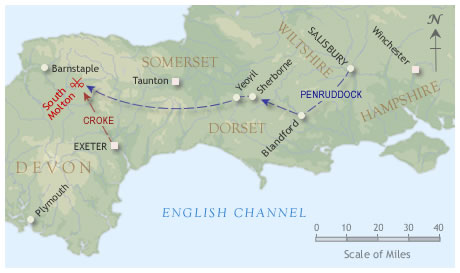

This was the Penruddock's Uprising and Sir Robert was right in the thick of it. As troops gathered across Wiltshire, Somerset, Dorset and Yorkshire, he would have ridden through Leicestershire into Nottinghamshire. The East of England was going to take the city of York, and Robert was one of the generals.

Except he wasn't.

Throughout Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire, he could not raise any support. Only 200 men gathered in Rufford Abbey, their rendezvous point; and most of them dispersed once it became clear that there weren't the numbers to fight.

As far as Sir Robert Shirley was concerned, his part in the rebellion was now a complete failure. It was rendered even more so when the Parliamentarians moved in. He was locked in the Tower of London once more.

Sir Robert Shirley in the Tower of London Part Two

One of the most prominent internees of the Royalist cause, he was given the job of raising funds for the King.

There is an alternative history often told about how Sir Robert ended up in the Tower of London in 1655.

According to this one, it was all because of the Chapel of the Holy Trinity. A letter came from Parliament, stating starkly, 'He that could afford to build a church, could no doubt afford also to equip a ship.'

It suggested a sum, which Robert refused to pay. He was arrested accordingly and imprisoned in the Tower. However, his arrest records, from June 1655, certainly accuse him of being part of the March Uprising. There is no mention of the church at all.

Robert was now aged 25-26. He was allowed a lot of freedom within the precincts of the Tower, including unsupervised visits from family and friends. He used the situation to fund-raise on behalf of the Sealed Knot.

This wasn't a great success. After a year of trying, he only managed to secure £60 for the exiled King Charles II.

Meanwhile, the Sealed Knot had largely fallen to pieces. No doubt it was the dire state of the rebellion, which persuaded Parliament to allow Sir Robert to leave the Tower of London on bail again. Not to mention the fact that they were getting rich off his broken securities; and he could lead them to more secret Royalist sympathizers.

Plans for an Anglican Insurrection at Staunton Harold Hall

The Sealed Knot would go into battle, under the banners of Laudian Anglicanism! It would be great!

Being back home gave Sir Robert the opportunity to commission the aforementioned ceiling in his church. He hired two local brothers, Samuel and Zachary Kirk, to paint it. Work continued with him personally over-seeing some of the fixtures and fittings. Another local man, William Smith, was employed for the next decade in making the pews, pulpits and communion table. He was also responsible for the over-hanging wooden joins.

A gate for the chancel was ordered from a famous Derbyshire iron-worker, Robert Bakewell.

But by now, Sir Robert Shirley seemed acutely aware of the hopelessness of the Royalist cause.

His personal correspondence, throughout 1655-56, sounds increasingly despairing. He tried to come up with solutions, but they weren't very feasible.

(One of them may or may not have been a plan to plant a bomb under Cromwell's dwelling. His name was attached to that conspiracy, in an intelligence report handed to the Protectorate, but there was no proof.)

The main thrust of his ideas was to organize under the banner of the Church of England. If the Sealed Knot could be reformed under the auspice of the Anglican vicars, then they would garner much more support.

Unfortunately for his religious idealism, most of them didn't seem to want to be involved. Robert's personal chaplain Reverend John Heavers signed up. So did a couple of bishops and two ordinary London clergymen. It was hardly an angelic host to lead the masses.

But his letters were also finding their way into the hands of Parliament. On September 2nd 1656, Sir Robert Shirley once again found himself arrested and taken back to his cell in the Tower of London.

Sir Robert Shirley in the Tower of London Part Three

This was to be his third and final stay in the infamous prison; and the Sealed Knot was back.

By October 1656, the Sealed Knot had risen from the ashes of defeat again. But this wasn't anything to do with Sir Robert Shirley.

Nevertheless, he was offered a place at its helm. The message was delivered to him in his cell. Sir Robert, unpredictable as always, asked for time to consider it. There was no indication given as to the problem. Maybe he was worn out. Maybe he felt disappointed that the same men had not flocked to his call, but went for other Royalist leaders. Or maybe the reason was much more personal than that.

On November 6th 1656, Sir Robert Shirley died in the Tower of London. The official news was that he'd contracted smallpox - the disease which had taken his father and elder brother - and it killed him.

Unofficial Royalist rumors maintained that he had been poisoned by Parliamentarian guards. He was twenty-six years old.

The Completion of Staunton Harold Church

The rest of Sir Robert's family finished the Chapel of the Holy Trinity. It survived Cromwell's armies.

Seymour Shirley, Robert's nine year old son, became the 5th Baronet of Staunton Harold Hall. It must have felt like history repeating itself, especially as he died in early adulthood.

His brother, Sir Robert Shirley, succeeded him. He was later to become Earl Ferrers and Viscount Tamworth, after Charles II was restored to the throne. In part, it was recognition for the role his father had played in the struggle. But it was also for his own service to Queen Anne.

As for the church, provision was made for its completion in its founder's will. Stonemason Godyer Holt was still working on the surrounding walls as late as 1667.

By then, the vault had long since been added. Sir Robert Shirley, 4th Baronet, was disinterred from his temporary resting place at Breedon Church; and he still lies under his church at Staunton Harold.

In 1672, he was joined by his long-suffering wife, Lady Katherine; then, one by one, by all of his descendants.

They weren't short of vicars. His same will had included a sum to distribute amongst all dispossessed and persecuted priests. Staunton Harold remained a safe house for them throughout the Commonwealth and into the Restoration. Laudian Anglicanism continued to be preached from the pulpit above, even after that became illegal.

But there was still one last addition to be made to the church - a sandstone mausoleum added to the grounds in 1906.

Sewallis Edward Shirley, 10th Earl Ferrers (and the last earl to live at Staunton Harold in high style) decided to double the size of the lake alongside the church.

Unfortunately, he didn't account for what that would do to the foundations. More particularly, how badly that would flood the vault, in which lay the remains of his ancestors. The damage was so extensive that it couldn't safely be opened to inter anyone else.

The 10th Earl simply built a small mausoleum in the grounds for himself and his wife. Lady Frances Eugenie Matilda Shirley (known as Ina Maude to her friends) was laid there in 1906. Her husband followed in 1912.

The shocking thing for modern sensibilities - devoid as we are of direct association with death - is that glass windows line both side walls. You can peer inside and see the lead coffins right there. A careful examination will reveal the crest of the Ferrers family embossed on both.